AN ABSOLUTE ORDER OF THINGS

АБСОЛЮТНЫЙ ПОРЯДОК ВЕЩЕЙ

In the contemporary cultural environment, Alexander Samoilov’s art, that has long ago surpassed far beyond its photographic limits, is an example of that uninterrupted tradition in the continuum of artistic thinking which for the majority of contemporary audience is considered as lost and for some even as never been really perceived. This tradition, however, is both contemporary and timely as it has never been before. It is defined by non-compromising status on the artist’s mission in the world’s artistic process and philosophical apprehension of it. Both the determination of artistic goal and the way of its realization play in this case the foremost role. This is the core of any creative process for real artists.

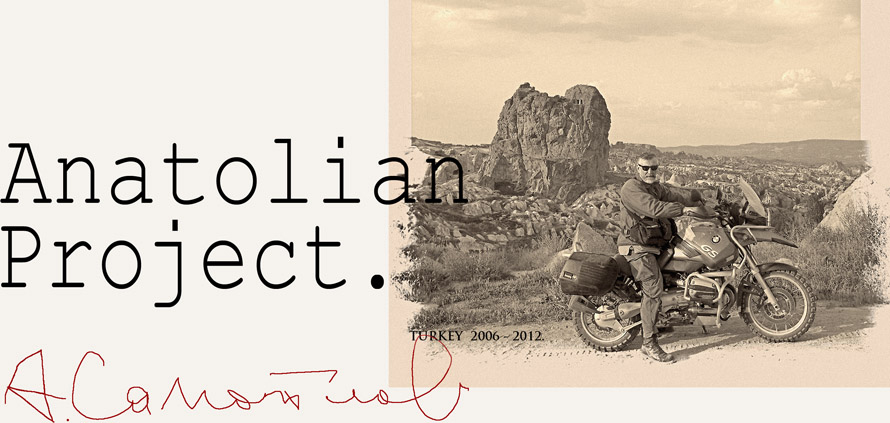

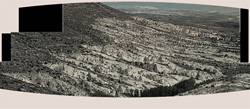

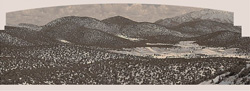

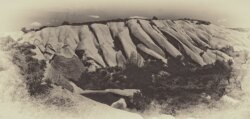

For quite a long time, this Russian photographer has been taking pictures on the territory of ancient Anatoila. These lands are literally filled with the cultural monuments of different civilizations including such a gem of the ellinstic culture as the ancient Pergam or the mountain of Nemrut-Dag with the sarcophagus of Antioche and the huge statues located there. The works that have been created by him within all these years are put together under a name of The Anatolian Project. To certain extent, this project elaborates the path of creative searches of such nineteenth century French photographers as Maxime Du Camp and Gustave Le Gray and also English photographers Francis Frith and John Beasley Greene. They first went to Egypt following archeologists and artists that began discovering the ancient civilization several dozen years after Napoleon campaign of 1801 and then also, to the other non-European countries.

Photographers of the second half of the nineteenth century had a powerful incentive, a scholarly research about Egypt called Description de l’Egypt that comprised 24 illustrated volumes and was published in France between 1809 and 1828. The pictures of Egypt, Palestine, Greece became popular among European viewers. Photographers would go on what was known as Grand Tours to take pictures of the ancient civilization monuments and those tours could last for several months. It should be also worth noting that photographers were certainly driven by desire of learning something beyond, the universe in the panhuman context – that universe of which Ralph Waldo Emerson in the 1840s suggested one should understand the nature in all its limitlessness and also the soul [of a learning man who himself is already the infinity].

What photographers had to face in Egypt, Palestine and Syria was a conceptually different. Space Having come from European civilization and having used to multi-floor buildings and cobbled sidewalks, they had to deal with the space that was not partitioned into segments of the city geometry with its familiar architectural dominants. They had to deal with the landform that was global and that suppressed everything around, with the grandiosity of virgin relief that spanned hundreds of miles far beyond the horizon. That was a different nature, a different topography. That was the space formed by millions of years, the cultural layer of which is rather its effect, the harmonious continuation.

The same we see in Alexander Samoilov’s Anatolian works – it is a massive topographic stratum that crushes all customary beliefs regarding the world order, it is the limitlessness of cosmos. You should define your own presence in this space, rationally relate yourself with it, with this humongous natural mass of power and meaning as Alexander von Humboldt thought of it. You should perceive the power of unity in its multitude and the harmony altogether.

Isn’t it in the cause of cognition and achieving the truth in its very inner meaning that the creative process is all about? Even if we agree that the French photographer Maxime Du Camp became fond of photography as not a means of self-expression but that of achieving the precision of reconstruction of the cultural values of the Egyptian civilization, he did yield to its capacities in the long run what made accompanying him Gustave Flaubert characterize the photographer’s work in one of his letters as not simply his fondness but “frenetic mania.” Wasn’t Flaubert’s characteristic meant to allude to Du Camp’s attempts to perceive, again and again, a photographed object as the topic for analysis of something more: that he wanted to measure his own thinking about the world and the cultural space that surrounded him and that had seemed so simple and clear before?

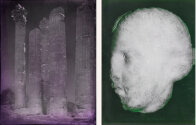

In 1852, an album, the first of its kind, called Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie with 125 photographs taken by Du Camp during his tours was published in France. Today, Du Camps’ photographs and those taken by another French photographer, Gustave le Gray, as well as photographs by two English, Francis Frith and John Beasley Greene, and by the Irish photographer, John Shaw Smith, (all of them actively worked in those lands) are not just the examples of photographic skill but they rather offer us the cause for a conversation about determination of the artistic goal and its problematics. Otherwise, how should we explain the fact that Le Gray chose not to photograph the columns of the Great Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Amun the way it had been done by Frith a decade before. What we see in Le Gray’s diagonals of light and shadow is not only his desire to show the grandiosity of creation of human hands but it is now a self-sufficient aesthetic form of unity of art and culture where the latter is supposed to be written with the capital letter. Paying tribute to Frith too, we should emphasize that epic extent of what appeared in front of him was probably so staggering that in his photographs he couldn’t help but underline the immensity of achievements of the ancient civilization with the elements of quite modest modernity…

In the 1960s, Erich Gombrich saw the reason for late start in researching of the territories of Greece by Europeans in the nineteenth century in the fact that it was a part of the Ottoman Empire. That significantly complicated access in there for archeologists and history researches let alone the territory of Small Asia itself that was called Anatolia in V-VI BCE. This peculiarity largely explains the fact of actual absence of the nineteenth century photographic documents created in Anatolia and therefore, a century and a half later, it cannot but impart evident significance to Alexaner Samoilov’s works.

Nevertheless, what matters is not really the time as such. Since the times of Du Camp and Frith, many things have changed and among them it is the way itself, a means of creation of artworks. It is the nature of humankind that with every new turn of the culture, artists return to old themes. For the most part it is predetermined by birth of a new, contemporary way of their representation. However, Alexander Samoilov didn’t simply find his individual way of solution. There is something other than that. He is a representative of the Russian culture and its inherent relationship with the subject of study. It is not the European linear approach. We deal with the culture in which the language aspect in the worldview formation is the key for development of juxtapositions; it plays the leading role in cognition and interpretation – it is when a mere communication, or communicative syntax, ideally will always concede to the form of order, to the functional syntax: when a means that expresses object-oriented relations becomes of great importance. In other words, this is the process of permanent juxtaposition and immersion into situation when it is ‘how’ what becomes of paramount significance and not ‘what.’

In Anatolian works of the photographer one should see an example of the photographic representation of that thinking process that is predetermined by precisely the specific character of both the order of his language and his culture when the goal is to not cease making self seek exceptionally the only one true formula of solving the theme. This is the ultimate task that leads on to the more high level of concepts and, consequently, of consciousness. Otherwise, the “violation of style” is imminent.

Such perspective is necessary for an adequate approach to Alexander Samoilov’s works as he is one of those few artists regarding whose oeuvre Oswald Spengler’s laconic characteristic of true art would be very appropriate to mention – “the self-evidence of the aim and un-self-consciousness of the execution.” In conversation about contemporary artistic space, such a formulation at times may seem rather irrelevant as the initial aims of many artists, if there are any, don’t comply with it at all. Postmodernism does its part. The visual art of today in all array of names representing it and genre varieties if ever may initiate any interest, it is rather in a conversation about simulacrum. However, the definition of artistic goal and artistic hierarchy is immutable. This is why the issues raised in The Anatolian Project are important as never before.

The creative act of Alexander Samoilov is what according to Nikolai Berdyaev “goes from within, from the fathomless and inexplicable depth and not from outside, not from the world necessity.” This journey of a thousand li began not with one step only but with a willful act that requires the presence of the goal, the issue, and the subject matter. His art is an act of freeing and overcoming, an act of experiencing the power. This is not about landscapes or simply making a photograph. This is about desire to break away, and the way out is the eternal and inconceivable beauty of the classics.

All his art is imbued with aspiration to follow the path of proving the necessary, unconditional obviousness of the determined goal. And the goal is constant striving to get closer to the mystery of the world’s beauty, desire to understand who we are and every other time, according to Alexander Samoilov, admit that “if we would find out who we are, our feelings would tear us apart. There is no meaning in it. The only meaning is the train of thought.” This is a sign of the intellectual art. And intellect, as Ralph Waldo Emerson said, requires an absolute order of things and without any touch of emotional character. This is The Anatolian Project.

Dmitry Kiyan

New York, 2010

В современном культурном пространстве творчество Александра Самойлова, давно вышедшего за рамки исключительно фотографические, есть пример той непрерывающейся традиции в континууме художественной мысли, которая для большей части сегодняшней аудитории представляется утраченной, а для кого-то и вовсе – непознанной. Однако эта традиция современна и своевременна как никогда.

В течение долгого времени русский фотограф снимает на территории древней Анатолии. Эти земли в прямом смысле насыщены памятниками разных культур: от античного Пергама, жемчужины эллинизма, до горы Немрут-Даг с гробницей Антиоха и огромными статуями на ней. Созданные за эти годы работы объединены названием “Анатолийский проект”. Отчасти этот цикл развивает линию творческих исканий фотографов середины девятнадцатого столетия: от французов Максима дю Кампа и Густава ле Грея до англичан Френсиса Фрита и Джона Бизли Грита, которые отправились сначала в Египет, вслед за археологами и художниками, начавшими открывать для себя “новый” мир через несколько десятков лет после наполеоновской кампании 1801 года, а затем и в другие неевропейские земли.

У фотографов второй половины девятнадцатого столетия был мощный побудительный мотив. В 1809-1828 гг. во Франции были изданы 24 научно-исследовательских иллюстрированных тома о Египте “Description de l’Egypt”. Виды Египта, Палестины, Греции стали популярны у европейского зрителя. Фотографы отправлялись на съёмки – “гранд-турне” – памятников древних цивилизаций, длившиеся по нескольку месяцев. Но стоило бы заметить, что ими наверняка двигало и познание большего: вселенной в общечеловеческом масштабе – той вселенной, под которой в сороковых годах девятнадцатого столетия Ральф Вальдо Эмерсон предлагал понимать природу во всей её безграничности, а также и души [познающего человека, который и сам по себе уже бесконечность].

С чем же столкнулись фотографы в Египте, Палестине и Сирии? С принципиально иным пространством. Им, вышедшим из европейской цивилизации, привыкшим к многоэтажным домам и мощёным тротуарам, пришлось иметь дело с пространством, не поделённым на сегменты городской геометрии с её привычными архитектурными доминантами, а с ландшафтом глобальным и всё подавляющим, когда на сотни километров вперёд за горизонтом простирается всё то же торжество девственного рельефа. Это была иная природа, иная топографика. Это было сформированное миллионами лет пространство, в котором культурный слой есть скорее его следствие, гармоничное продолжение.

То же и в анатолийских работах Александра Самойлова: мощная, сокрушающая все прежние представления о мироздании ландшафтная порода – безграничие космоса. И в этом пространстве нужно определить своё положение, рационально соотнести себя с ним, с этой огромной природной массой силы и смысла, как смотрел на это Александр фон Гумбольт, необходимо постичь мощь единства во многообразии и гармонию в целом.

Разве не ради познания, извлечения истины в самом глубинном понимании этой задачи и есть цель творческого процесса? Если и допустить, что француз Максим Дю Камп увлёкся фотографией не как средством самовыражения, а способом добиться точности реконструкции культурных ценностей египетской цивилизации, то в конечном итоге не устоял-таки он перед её возможностями, что заставило сопровождавшего его Густава Флобера в одном из своих писем охарактеризовать работу фотографа не просто увлечением, а “неистовой манией”. Не на то ли намекал Флобер, что дю Камп раз за разом пытался вникнуть в фотографируемый им предмет уже как в тему для анализа большего: хотел сопоставить прежде казавшееся таким понятным и ясным собственное представление о мире и культурном пространстве?

В 1852 году в количестве около двухсот экземпляров во Франции был издан первый в своём роде альбом “Egypte, Nubie, Palestine et Syrie” со 125 фотографиями, сделанными дю Кампом во время своих путешествий. Сегодня они, а также фотографии другого француза, Густава ле Грея, и активно снимавших в тех же землях англичан Френсиса Фрита, Джона Бизли Грина, ирландца Джона Шоу Смита представляют собой пример не просто фотографического мастерства, но скорее дают повод именно для разговора о постановке художественной задачи и её проблематики. В противном случае, как понимать то, что ле Грей, в 1867 году предпочёл не снимать колонны гипостильного зала в храме Амона так, как сделал это Фрит десятилетием ранее. В диагоналях света и теней у ле Грея видится стремление передать не просто грандиозность творения рук человека – это уже самодостаточная эстетическая форма в единении искусства и культуры, где второе подразумевается с прописной буквы. Отдавая должное и Фриту, следует заметить, что эпический размах представшего перед его глазами был, по всей видимости. настолько сокрушителен, что он нередко стремился подчёркивать масштабность достижения древней цивилизации элементами весьма скромной современности.

В шестидесятых годах двадцатого столетия Эрнст Гомбрих причину поздней исследованности территорий Греции европейцами девятнадцатого столетия справедливо видел в том, что она была частью Османской империи, а это весьма затрудняло доступ туда археологам и историографам. Что уж говорить о собственно территории Малой Азии, носившей название Анатолии в V-IV вв. до н. э. Данная особенность во многом объясняет факт практического отсутствия фотографических документов девятнадцатого столетия, созданных в Анатолии, что по прошествии с тех пор полутора столетий уже одним только этим не может не придать очевидной значимости работам Александра Самойлова.

Однако, дело не только во времени как таковом. Со времён дю Кампа и Фрита поменялось многое и среди прочего – собственно способ, средство создания произведения. На каждом новом витке культуры человек, так уж он устроен, возвращается к прежним темам. И во многом это обусловлено рождением нового, современного способа их отображения. Но Самойлов не просто нашёл своё индивидуальное решение. Тут иное. Перед нами представитель русской культуры и соответствующего ей отношения к предмету познания. Это не по-европейски линейный расчёт. Мы имеем дело с той культурой, при которой языковой аспект формирования мировоззрения выступает в качестве ключа к развитию сопоставлений, играет первостепенную роль в понимании и трактовании – когда просто коммуникативность, или коммуникативный синтаксис, в идеале иерархически будет всегда уступать форме строя, синтаксису функциональному, при котором чрезвычайную важность приобретает то, какими средствами выражаются целевые отношения. Иными словами, это процесс постоянного сопоставления и погружения в ситуацию, при котором первостепенную значимость приобретает не “что”, а “как”.

В анатолийских работах фотографа следует видеть пример фотографического отображения процесса мышления, обусловленного именно спецификой строя его языка и культуры, когда цель – не переставать заставлять себя искать единственно верную форму решения темы. Это есть сверхзадача, выводящая на более высокий уровень понятий и, как следствие, сознания. Иначе – неизбежность “нарушения стиля”.

Данная перспектива необходима для адекватного отношения к работам Александра Самойлова, ибо он один из тех немногих художников, применительно к творчеству которого уместным будет вспомнить лаконичную шпенглеровскую характеристику признаков истинного искусства – самоочевидность художественной цели и простота исполнения. В разговоре о современном художественном пространстве данная формулировка порой кажется уже и неуместна, настолько несоответствующими ей видятся изначальные установки многих авторов, если таковые и вообще существуют. Постмодернизм делает своё дело. Сегодня визуальное искусство во всей массе представляющих его имён и жанровых разнообразий, если когда и вызывает интерес, то разве что в разговоре о симулякруме. Однако же, понятие художественной цели и творческой иерархии неизменно. Именно поэтому темы, поднимаемые в “Анатолийском проекте” актуальны как никогда.

Творческий акт Александра Самойлова есть то, что по Бердяеву “идёт изнутри, из бездонной и неизъяснимой глубины, а не извне, не из мировой необходимости”. Эта дорога в тысячу ли была начата не только лишь с одного шага, но с волевого акта, требующего наличия цели, предмета, содержания. Его творчество есть освобождение и преодоление, переживание силы. Это не вопрос пейзажа, просто изготовления фотографии, а желание вырваться, и выход – вечная, непостижимая красота классики.

Всё его творчество пронизано стремлением идти по линии доказательства необходимой, безусловной очевидности поставленной цели. И цель – постоянное стремление приблизиться к тайне красоты мира, желание понять, кто мы, и раз за разом, согласно Самойлову, признавать: “Если бы мы сразу узнали кто мы, чувства наши нас разорвали бы. Смысла в этом нет. Весь смысл в движении мысли”. Это признак интеллектуального творчества. А интеллект, как утверждал Эмерсон, требует абсолютного порядка вещей и без какого-либо оттенка эмоционального характера. Это и есть “Анатолийский проект”.

Дмитрий Киян

Нью-Йорк, 2010 год